Following the publication of Growing the good, Nusa Urbancic of Changing Markets sets out the case for Governments to include emissions from agriculture in their climate targets. In this article Nusa explains the need to provide a clear trajectory to realise the huge potential benefits these dietary shifts could have in terms of climate and health outcomes:

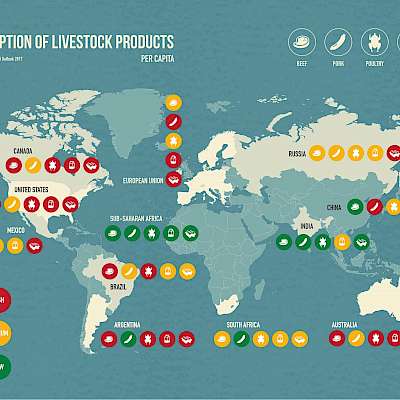

Our overconsumption of meat and dairy products has been in the spotlight following the publication of the latest IPCC report, which warns that we have 12 years to avert catastrophic climate breakdown. And rightly so: animal agriculture is a large source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but is at the same time one of the first victims of climate change whose impacts are already showing their teeth in the shape of increased droughts, floods and other extreme weather events. Reducing our consumption of meat and dairy in response to the threat posed by climate change represents a unique opportunity to shift our agricultural systems towards the production of less and better meat and dairy. Numerous studies have shown that a significant reduction in consumption and improved production must go hand in hand.

Changing Market’s recent report Growing the good highlights the absence of policies to facilitate this transition towards ‘less and better’ meat and dairy and reduce GHG emissions from agriculture. Unlike in the energy and transport sectors, where we have a variety of policies to drive companies, consumers and investors towards low carbon options such as renewable electricity and electric vehicles, farming subsidies still mostly support intensive farms. The bulk of agricultural subsidies in Europe (worth around £53 billion a year) goes towards intensification, which makes agriculture the main driver of species and habitat loss. The situation is so bad that many ‘high nature value farmers’, who are struggling to stay in business, say they would prefer no subsidies at all so that they could at least compete more fairly with industrial farmers. The vast majority of coupled support in this flawed system goes to the meat and dairy sectors.

Such use of subsidies stands in stark contrast with market trends and public opinion. Plant-based products are one of the fastest growing food categories with an annual growth rate of 5-10% in the UK – in a market that is already worth over £3.6 billion globally. In addition, a third of the British population now identify either as vegan, vegetarian or as reducing their meat intake. Regardless of individuals’ personal reasons for doing this, policies encouraging this consumer trend would be of great value to national health systems: a recent study showed that taxing meat as a harmful product across rich countries could recoup about half of the £223bn spent every year around the world treating illnesses caused by eating processed and red meat. Governments have already put numerous similar measures in place (taxing tobacco, sugar, petrol, etc.) and people usually accept these measures, when the harms are properly explained to them and when convenient alternatives are available.

So in light of the burgeoning market for meat alternatives, consumer trends and overwhelming scientific evidence of the numerous win-win-win effects that such policies could have, we are left with the question: why are governments so reluctant to act? Our research shows that as in other sectors, there is strong and organised opposition by the interests that benefit from the status quo. Conventional farmers and meat producers have already lobbied for legislation to restrict market growth of meat alternatives, such as the recent French law which bans the use of the terms ‘burger’ and ‘sausage’ for anything that is not of animal origin. Such policies are short-sighted and in direct opposition to governments’ international commitments to halt climate change and biodiversity loss.

Instead of succumbing to pressure from the meat lobby, governments should take bold action to include emissions from agriculture in their climate targets and set a clear trajectory to realise the huge potential benefits these dietary shifts could have in terms of climate and health outcomes. Food is a sector with constantly shifting consumer preferences where transformation can happen quickly. If high income country’s governments who are also major importers of high-carbon and resource-intensive products, lead the way, a managed transition can have positive repercussions on land use, nature systems and emissions globally. At a time when we really need it.

Here in the UK, Eating Better is working with Sustain on submission to Climate Change Committee’s Net Zero Call for Evidence. If you want to contribute, please get in touch - [email protected].