We are delighted to announce that the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), is joining the Eating Better Alliance. RSPH is a respected and storied institution but behind its brass plaque and grade II listed building is a small and focussed team. Shirley Cramer, RSPH’s Chief Executive, is clear that poor nutrition and bad food environments are a public health issue. We spoke to her about RSPH’s second ‘Health on the High Street’ report and recommendations for healthier food environments and, in the wake of the EAT Lancet report, about how the wider food system needs to change without leaving less well-off families behind.

"We support the Eating Better Alliance and for a public health organisation it’s good to be a member. We care a lot about obesity and health inequalities. The trends are going in the wrong way. Poor children are far more likely to be obese”. Shirley Cramer.

Chicken shops and betting shops - the high street is struggling. Why should we care?

Nearly anything you want or need can be bought and delivered without leaving the home. It might seem we could live without high streets. But what would the cost be to our communities? High streets are the focus of every town and city in the UK. But because of competition from online sales, huge numbers of shops are empty, or given over to fast food outlets and betting shops, creating environments that have a negative impact on health.

“Yes, the high street is a community asset. Can we have differential business rates? Or taxing? There are organisations trying to deliver healthy fried chicken, with good provenance, better oils. It’s healthier but still a tasty version. That should be applauded by those in the community. In fact, local government is doing a lot in this area but is really starved for cash. There’s a point at which it’s really hard to innovative when you have no funding”. Shirley Cramer.

In countries like the UK, having healthy, affordable food on the high street is of great benefit to lower-income people. This is because high-income countries generate ‘food deserts’ characterised by a relative lack of healthy and nutritious food options and ‘food swamps’ characterised by an excess of fast food chains and food outlets selling processed foods (see The Lancet’s excellent recent report on the global obesity syndemic). Sadly, Britain’s food deserts and swamps are a real and pressing problem, entrenching poverty and contributing to the surge in food bank usage.

RSPH’s 2018 ‘Health on the High Street’ report calls for a big shift in business regulations which currently enable bad food environments, including fairer taxation of online companies and powers for councils to set rent classes for tenants based on how health-promoting their business offer is.

Can lower income families afford the EAT Lancet diet? Time to stop blaming families and individuals for systemic failure.

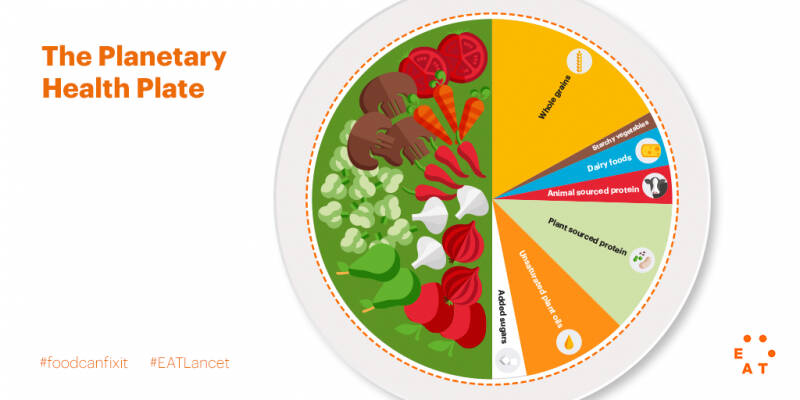

Eating Better supports the EAT Lancet Commission’s recent report, which brings together comprehensive evidence on why a diet with lower meat and dairy consumption and less processed food is better for health and the environment. The EAT Lancet report doesn’t answer every question, but it is sensitive to different view points, whilst calling for a halt to the obesity epidemic and setting a route to meet the Paris agreement targets for global warming.

Many will have been surprised by the news that a third of Brits now have meat-free or meat-reduced diets. But at the same time, because of the widening gap between rich and poor, lower income families are missing out on the healthy food revolution.

In November last year, the Health Secretary Matthew Hancock disappointed many in the public health community by shifting responsibility for health onto individuals, rather than talking about ways to fix the system. Policy makers need to understand that unhealthy food choices arise from a combination of low income, being time-poor and lacking access to healthy food.

Professor Martin Caraher, who helped create the food strategy for London, explains that during the 2008 recession, high and middle income families ate out less, but low income families ate out more, because they relied on cheap fast food. Having children adds to the pressure. The Government’s Childhood Obesity Strategy, notes that 68% of households with children under 16 had eaten takeaways in the last month, compared with only 49% of adult-only households.

To explain why people are effectively locked into choices they know are unhealthy, we need to look at the way the UK food system is set up. We are obsessed with spending as little as possible on food, and have the lowest average spend in the world outside America and Singapore. To maintain this, we rely on a supply chain which provides the cheapest food in western Europe, which has inevitable consequences for quality.

Government figures show that the percentage of spend on food continues to be highest in households with the lowest 20 per cent of income. At the same time, food comes after housing, fuel and power costs. In other words, when incomes fall and bills rise, spending on food gets squeezed. ‘That’s why mum’s gone to Iceland’, the old slogan ran.

The Government’s Eatwell Guide rightly advises reduced red and processed meat consumption, but last month, The Food Foundation’s Broken Plate report showed that the Eatwell diet would require the poorest 10% of households to spend three quarters of their disposable income on food. It just doesn’t add up.

These financial pressures exist in a wider context where there is a concentration of fast food outlets in poorer areas and lack of access to local shops or supermarkets supplying fresh fruit and vegetables.

While young people are being channelled into making bad food choices, we shouldn’t assume they are happy to do so. RSPH’s Child Obesity Strategy found that 71% of young people say food high in fat, salt or sugar should come with a health warning and that 75% believe takeaways should make the healthier meal deals cheaper than the unhealthy ones.

This is a point that Shirley Cramer is very keen to reinforce:

“The cheap, cheap food goal is the wrong goal. I think it’s a false dichotomy promoted by producers and purveyors of high salt, fat and sugar. There is evidence from polling that people know we need to pay more. We should be subsidising fruit, vegetables and pulses to make them less expensive. Make the food people really need and will be health-promoting. Not the £1.99 fried chicken and fries. It’s terrible, the presumption that people on low incomes don’t want to feed their kids better. As a society it’s our responsibility that there’s good food available.

We’re allowing the big providers, the global firms to get away with it, because they’re using the ‘cheap as possible’ argument. It’s not what communities tell us. What we don’t want is these huge variables: ‘I can only afford fruit and vegetables at the beginning of the month.’ It’s lazy thinking that better food at a higher price wouldn’t be fair on poorer communities. Because you’re just saying they deserve a diet of rubbish”.

As well as being the Chief Executive of RSPH, Shirley sits on the RSA’s Food Farming and Countryside Commission. She told us the Commission is looking at how the UK food production system needs to change:

“We should incentivise farmers like we do other industries. Of course, the Common Agricultural Policy will be gone. What are we going to subsidise and how are we going to help farmers to retool? EAT Lancet will help us look at tradeoffs. As Eating Better says, around meat dairy, pulses. We won’t please 100% of people but we can get a better food system, much more holistic and local. It’s about providing good quality food at a price people can afford. Have the discussion. What are people willing to trade to get the right mix? Farming isn’t my expertise, but everyone on all sides of the discussion agrees farmers need to be paid more. Look at the food chain; it’s not transparent. Everyone adds their bit on and the farmer isn’t paid enough. We need to look at the value chain and how it works”.

RSPH and Eating Better working together.

Eating Better is keen to connect with the public health community, so we’re excited about what RSPH can add to the Alliance. Shirley Cramer’s optimism and energy for changing the debate has already gained an audience on food issues and RSPH isn’t afraid to challenge the status quo. At the same time, RSPH has a broad remit and can benefit from Eating Better’s ability to make the evidence-based case for less and better quality meat in people’s diets.

By Daniel Knag for Eating Better

With thanks to Shirley Cramer.

Images courtesy of: RSPH.